Posts tagged with “wisdom”

Why Relationships Matter Most: We’re All Just Walking Each Other Home

“We’re all just walking each other home.” ~Ram Dass

Living in the hyper-individualist society that we do, it’s easy to forget our obligation to those around us. Often in the West, we are taught to prioritize ourselves in the unhealthiest ways, to ‘grind’ as hard as we can to achieve wealth and status.

We are taught, between the lines, that our first responsibility is to create a ‘perfected‘ version of ourselves to such an extreme that it is alright to forsake our relationships with others to accomplish it.

From day one, it is embedded in us that it …

How to Ease the Pain of Being Human: From Breakdown to Breakthrough

“Nothing ever goes away until it has taught us what we need to know” ~Pema Chödrön

We are all works in progress.

We all have skeletons in our closets that we may wish to never come out. We have all made mistakes. We will all make mistakes in the future. We all have our scars.

None of us are close to reaching that mythical ‘perfect’ status. Never will be.

None of us should consider ourselves fully evolved. Not even close. There will always be space for improving an area of our lives.

Truth be told, most of us are a …

How Yoga Helped Heal My Anxiety and Quiet My Overactive Mind

“The privilege of a lifetime is to become who you really are” ~Carl Jung

Yoga is often celebrated for its physical benefits: greater flexibility, increased strength, improved circulation, and so on. But nothing could have prepared me for the transformational effect that yoga has had on my mental health and well-being.

I was diagnosed with anxiety and depression when I was fourteen, and I have struggled with both for most of my life. My mind was my worst enemy, constantly worrying and criticizing to the point where it became hard to do anything. Even the things I really wanted to …

Trust Restored: Why I’m Letting Go of Preconceived Ideas About People

“The problems around us are only compounding. We will need to rediscover our trust in other people, to restore some of our lost faith—all that’s been shaken out of us in recent years. None of it gets done alone. Little of it will happen if we isolate inside our pockets of sameness, communing only with others who share our exact views, talking more than we listen.” ~Michelle Obama

I’m up at the American River, one of my favorite summertime spots. I have a ritual of floating down it, then hiking back up the hill to my clothes. I love how …

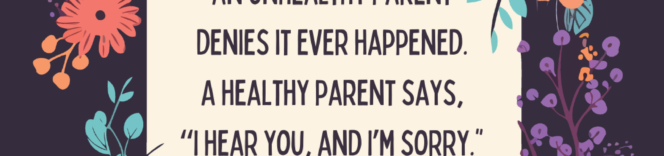

“But He Never Hit Me!” – How I Ignored My Abuse for 30 Years

“People only see what they are prepared to see.” ~Ralph Waldo Emerson

Abuse is a funny thing. I don’t mean humorous, of course.

I mean the other definition of funny: difficult to explain or understand.

Abuse shouldn’t be difficult to understand. If someone is mistreated, we should be able to clearly point a finger and proclaim, “That is wrong.”

But not all abuse is obvious or clear-cut.

I was abused for most of my adult life and didn’t know it.

Crazy, right?

Let me state it again: I was abused and didn’t know it.

I only saw what I …

How To Make Peace with Regrets: 4 Steps That Help Me Let Go

“Under any circumstance, simply do your best, and you will avoid self-judgment, self-abuse and regret.” ~Don Miguel Ruiz

The other day, I told my adult niece that I regretted selling my downtown condo several years ago.

“On no,” she said. “You told me back then that you were finding the lack of light was getting to you. You weren’t happy there.”

I had no memory of that until she reminded me. And surprisingly, it lifted a great deal of my painful regret around it. It helped me change from regret to recognition that I’d made the right decision.

That got …

How I’m Overcoming Perfectionism and Why I’m No Longer Scared to Fail

“Perfectionism is a self-destructive belief system. It’s a way of thinking that says: ‘If I look perfect, live perfect, and work perfect, I can avoid or minimize criticism and blame.’” ~Brené Brown

I struggled with trying new things in my past. I learned growing up that failure was bad. I used to be a gifted child, slightly ahead of my peers. As I got older, everything went downhill.

Whenever I tried out a new activity, I would quit if I wasn’t instantly perfect at it. If there was the slightest imperfection, I would get extremely frustrated and upset. I …

Though I run this site, it is not mine. It's ours. It's not about me. It's about us. Your stories and your wisdom are just as meaningful as mine.

Though I run this site, it is not mine. It's ours. It's not about me. It's about us. Your stories and your wisdom are just as meaningful as mine.