Note: The winners for this giveaway have already been chosen. Subscribe to Tiny Buddha for free daily or weekly emails and to learn about future giveaways!

The Winners:

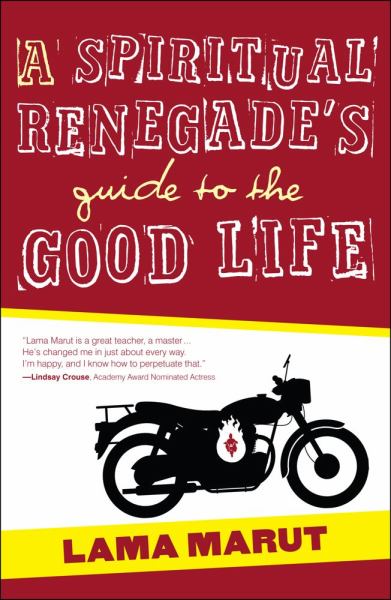

Though we may all have varied goals and paths, ultimately, we all have the same objective: happiness. It’s with this in mind that Buddhist monk Lama Marut wrote A Spiritual Renegade’s Guide to the Good Life.

Through a series of meditations, exercises, and insights, he helps us overcome suffering and create contentment—two essential prerequisites to happiness.

Playful and entertaining, A Spiritual Renegade’s Guide to the Good Life distills complex ideas into a light-hearted, easy-to-read manual for happiness and fulfillment.

I’m grateful that Lama Marut took the time to answer some questions about the book, and also offered 5 books for Tiny Buddha readers.

The Giveaway

To enter to win 1 of 5 free copies of A Spiritual Renegade’s Guide to the Good Life:

- Leave a comment below

- Tweet: RT @tinybuddha Book GIVEAWAY & Interview: A Spiritual Renegade’s Guide to the Good Life http://bit.ly/TuAGfP

If you don’t have a Twitter account, you can still enter by completing the first step. You can enter until midnight PST on Tuesday, December 4th.

The Interview

1. What inspired you to write A Spiritual Renegade’s Guide to the Good Life?

I wanted to try to summarize—in ordinary, non-technical language—what I had learned over the years about living a life conducive to happiness. We are all driven by the desire to be happy, but I know in my own case that I spent a lot of time barking up many wrong trees before I found a method that really worked!

2. How do you define “the good life”?

The phrase has a double meaning. It means, firstly, a happy life in which we have good relationships, a secure financial situation, a rewarding profession, healthy self-image, etc.

The way to achieve the good life in this first sense is to live the good life in a second sense: to lead a moral life based on non-violence, telling the truth, not taking what doesn’t belong to you, being generous, etc. You reap what you sow; what goes around comes around. If you want to have a good life in the first sense of the term, you must live the second kind of good life.

3. In Chapter One, you wrote that we sometimes think of happiness as a selfish goal. Why do you think we believe this, and how can we move beyond it?

I think one of the little demons inside our own heads that tries to trash our quest for true happiness is a wolf in sheep’s clothing: “I thought you were supposed to be a good person who cared about others,” that demon might say, “and here you are selfishly pursuing your own happiness.”

That’s a devil that really needs a talking to, for the logic is totally faulty. We know from experience that it’s only when we feel happy ourselves that we clear the head-space for taking real interest in others.

We can’t really be of much use to other people if we haven’t fixed ourselves first. We can’t help save the drowning unless we know how to swim; we can’t be helpers if we remain “helpees.”

4. You wrote that the entry point for happiness is contentment. Can you expand on this?

I think sometimes when we imagine what it would be like to be happy—let alone when we are picturing a religious goal like “nirvana” or “samadhi” or “salvation”—we imagine some kind of ecstatic state. Like the goal is to be blissed out all the time or something.

I’m not sure that being blissed out all the time is possible or even desirable, but in any event it seems clear that if we are to reach higher states of happiness—joy, bliss, euphoria, ecstasy, or whatever—we must first achieve good old simple contentment.

We’re unhappy because we are dissatisfied with life and are driven by greed, aversion, and grasping. As the Buddha said, we suffer because we don’t get what we want, we do get what we don’t want, and we lose what we want to keep. Contentment is the opposite of this perpetual dissatisfaction.

5. In Chapter Four, you explored what forgiveness is and what it isn’t. What’s a common misconception about forgiveness that keeps us stuck?

On my book tour last summer, I took to calling forgiveness the “f-word,” because every time I started to talk about it I got a reaction similar to the response I would have received had I been using the other “f-word.” Major aversion. Nobody wants to forgive. We have huge resistance to it.

I think our reluctance to forgive depends on harboring a set of false ideas. One of these is the notion that by not forgiving the person who hurt us we are somehow hurting them back.

We justify our refusal to forgive by thinking of it as retaliation. But this is completely wrong-headed! It’s been said that not forgiving is like drinking poison in the hopes that someone else will drop dead. Not forgiving doesn’t hurt anyone other than ourselves.

6. Later you suggested that we can be grateful for our difficulties. How can we shift to a mindset of gratitude when we’re feeling hurt and bitter?

Gratitude depends on feeling that there’s something to be grateful for. So the trick when it comes to being grateful for what would otherwise just be a source of suffering is to try to see something useful in the event.

If we can reinterpret what we may be tempted to see as just a problem into an opportunity to learn something and to grow into better human beings, we can then feel gratitude to those who made that beneficial (if somewhat difficult) experience possible for us.

7. What did you mean by “All history is revisionist history”?

There’s no story about the past—neither any “official” narrative like the ones our professional historians tell, nor any of the stories we tell ourselves about our own individual past—that isn’t being told from the present perspective.

And since the present perspective is constantly changing—time does, after all, march on—there is no story about the past that isn’t changing too.

The past and the present exist interdependently. We are who we think we used to be, and we think about how we used to be in terms of who we think we are. Both. So change one, you change the other.

Revising our history by seeing it through the lens of forgiveness and gratitude instead of bitterness and resentment will automatically improve the way we think about our present.

8. You wrote that it’s okay to “think about the future in a wise and healthy-minded manner.” What’s the difference between doing that and trying to control the future?

Often when we think about the future we worry about all the things that could go wrong. But the future rarely, if ever, turns out to be the way we imagined it, so it’s foolish to buy into all the nightmarish scenarios our imagination conjures up.

We can have trust that everything will be all right in the future if we are attentive to creating favorable causes with our actions in the present. Live a morally good life, and then have some faith in the process!

What goes around will come around, so if we’re careful about what we put out there we can think about the future with confidence that it everything will be okay.

While we can’t predict the specifics of what will happen (and who would really want to anyway?), we can in general rest assured that if we have created good causes, good effects will follow.

9. What’s the main message you hope readers take from this book?

I would hope that readers would take away the belief that true, deep-seated happiness is really possible and that the means for achieving it are entirely in our own hands.

If we feel ourselves to be hapless victims of others’ actions or of the randomly unfolding vicissitudes of life, or if we presume that it someone else’s job to make us happy, then we totally disempower ourselves.

We have the possibility, even the right, to be happy in life, but we must be spiritual renegades, take the bull by the horns, and do what’s necessary to attain our goal.

Learn more about A Spiritual Renegade’s Guide to the Good Life on Amazon.

FTC Disclosure: I receive complimentary books for reviews and interviews on tinybuddha.com, but I am not compensated for writing or obligated to write anything specific. I am an Amazon affiliate, meaning I earn a percentage of all books purchased through the links I provide on this site.

About Lori Deschene

Lori Deschene is the founder of Tiny Buddha. She started the site after struggling with depression, bulimia, c-PTSD, and toxic shame so she could recycle her former pain into something useful and inspire others to do the same. You can find her books, including Tiny Buddha’s Gratitude Journal and Tiny Buddha’s Worry Journal, here and learn more about her eCourse, Recreate Your Life Story, if you’re ready to transform your life and become the person you want to be.

- Web |

- More Posts

Though I run this site, it is not mine. It's ours. It's not about me. It's about us. Your stories and your wisdom are just as meaningful as mine.

Though I run this site, it is not mine. It's ours. It's not about me. It's about us. Your stories and your wisdom are just as meaningful as mine.

Omg! I want this book!

I can’t wait to read this book! Ven. Marut’s wisdom has offered me so much to look forward to! A big thank you!

I’d love to give this book a read!

I’m looking to re-evaluate what is really important to me in the coming months, so I think this book would be a perfect read right now!

I’d love to read this.

Nice interview and the book seems even MORE interesting! The title, according to me is really catching. ‘The spiritual Renegade’s’ 🙂

This book looks so cool!! I would love to read and review it!! Please enter me into the giveaway pool!!

I would love to read it.

Be bold, be bold, and everywhere be bold. Bold in seeking your spiritual truth and happiness.

This sounds like an awesome book. Please enter me in the very generous give-a-way! My fingers are crossed. It does sound like just what I need.

Thank you!

Sounds like a great book!

I never realized that I thought Happiness Was a selfish thing until I read it here, but it has Always been my Number One Nightly Wish Upon a Star wish.

I like what I have read here very much and would love to read this book and put it into practice. Then I can share it with my daughter, she needs the Instructions for a Happy Life too!

Thank you for your great blog, it is one of my Must Reads every day and I have shared it with Many – Kudos! & please keep it coming.

i need to stockpile my library for maternity leave. this looks fantastic

“Revising our history by seeing it through the lens of forgiveness and gratitude instead of bitterness and resentment will automatically improve the way we think about our present.” Brilliant statement! Taking this to heart and practicing it has the potential to change one’s life dramatically! Wow.

These are guiding principals that I am working on for both myself and to show to my son. Every new insight helps, thanks.

As usual, this post hit me at the perfect time. Trapped at home without a car (and unable to drive anyway due to a broken foot), this book would be a fabulous and so pertinent read for me! Thanks for introducing me to it, and for the chance to win a copy. 🙂

I really appreciated the lessons in forgiveness and revising our history – which also required forgiveness – forgiving ourselves. Thank you for this lovely read and this looks like a book that is a must read in my near future 🙂

Contentment is the best kind of happiness. It feels warm and right.

Thanks! G.

I work hard every day to live my life in the “second sense:” with honesty and compassion. Would LOVE to read this book!

I love books like this. I can always find a gem that helps me work through another knot in my life.

Contentment is peace and that is happiness. You might be going through the toughest of times, bt if you feel stillness inside you are happy. I have recently experienced this feeling in glimpses as I have let go on expectations I had from my better half and I feel so lighter. Today i wonder why did i send countless nights crying and wondering why he thinks like that..why he doesnt share our future plans with me….when all this time answer was with me…

Would love to read this book…

I’ve been struggling to accept the end of a 10 yr relationship with my boyfriend. I think this book would be a very beneficial read for me right now. Please enter me in the giveaway. Thanks!

I like the title, “Spiritual Renegade”!!!!!!!!!

Wow,this post hit home. I will definitely need to read this book!

Excellent interview; looks like it will be a good book.

Sounds like an awesome read and one that I would greatly benefit from at this point in my life.

I really enjoyed reading this. I like the definition in #2 and I think I’m going to use that in one of my upcoming blog posts. Thank you.

A key point for me is that the past only exists in memory, and memory is fallible and changeable. Those things that still pull at us don’t even exist anymore. It’s all in our heads.

Thank you for needed advice at this time in my life…

Love that guy. I discovered him via Nick Hexum of the band 311. Im hoping you discovered him from my retweets!

I would love to read more about his concept of forgiveness. I have trouble with forgiveness and he seems to understand. (love that he calls it “the f-word”–funny).

Looking forward to reading your book! Really enjoyed the blog post!

if we presume that it someone else’s job to make us happy, then we totally disempower ourselves – so true

Looking forward to this great read!

This sounds like a great book!

I would be forever grateful to you for being selected to receive a copy of this book. I’m on my journey and almost at the end of a horrible divorce after 30 yrs. I’m working and growing each and everyday while on the other side…some things never change. So happy with my decisions but always looking for additional help to get me through the process. Thank you for being so generous!!!!!!

Namaste

I’d love to win this book (like everyone else). I do love what he says about the F word. I am struggling with that.

I am interested to find out what the author says about the standard of morality, not being happy when we don’t get what we “want” (I don’t get that at all. Not getting what I “want” has no play in my happines). I have never believed in “come around, goes around” otherwise crime wouldn’t pay so well. I would like to read the author’s take on those things and more.

“I’m not sure that being blissed out all the time is possible or even desirable, but in any event it seems clear that if we are to reach higher states of happiness—joy, bliss, euphoria, ecstasy, or whatever—we must first achieve good old simple contentment.”

–>AGREE. Although if I could find a way to make my yoga buzz last all day, I would be more than content, that’s for sure!

I would love to win this! I am someone who is always grateful for my difficulties – they provide me with opportunities to grow! I would love to hear the author’s take on this!

I would love a chance to read this. Fingers crossed!

I really need to work on the being grateful for the non-fun parts of life! I have a lot to be grateful for lately.

This looks like an amazing read!

Thanks for sharing this interview with us – what an interesting and accessible approach! This books is on now on the reading list!

Thank you for giving us the opportunity to discover this book. Who would not like to have a guide to a better and happier life? Not me…

I would definitely enjoy reading this book!

Sounds like a great no-nonsense book I’d love to read and be inspired by!

I’m with Bontainblue – definitely added to the reading list. Thanks for the interview.

Having been in a major depression for way too long, I think that this book might be incredibly useful to me. Attaining “just” the level of contentment seems like Nirvana to me! Yes, am in treatment, but not improving as I should be. I’d love to be in the drawing, too! Thanks, and Thanks to Lori for creating Tiny Buddha!