“We need to learn how to navigate our minds, both the good and the bad, the light and the dark, so that ultimately, we can create acceptance and open our arms and come home to ourselves.” ~Candy Leigh

Divorce is so common that my son, at a young age, asked if my husband and I could divorce so he could have “a mom’s and dad’s house too!” And my daughter agreed because then “we could get double presents on holidays!” Given my experience as a child with divorced parents, I assured them, “Guys, divorce is not really that much fun.”

The truth is there is nothing romantic about divorce for the parents or the children. When a family breaks up it becomes de-stabilizing for everyone. Suddenly, how things were disappears and everything feels tilted. Like being on one of those “tilt-a-whirl” amusement park rides where you just want it to right itself so you can feel better.

Home doesn’t feel like home anymore in the way one knew it. A mother’s kitchen may have no child at Christmas. A parent’s bedroom looks different with someone missing.

I remember before my parents divorced, I noticed a sign. Their bed was actually two twin beds pushed together. But in the year before the divorce the beds were separated. Soon, my dad wasn’t around on Sunday mornings to make me bagel and bacon sandwiches, and our house echoed emptiness.

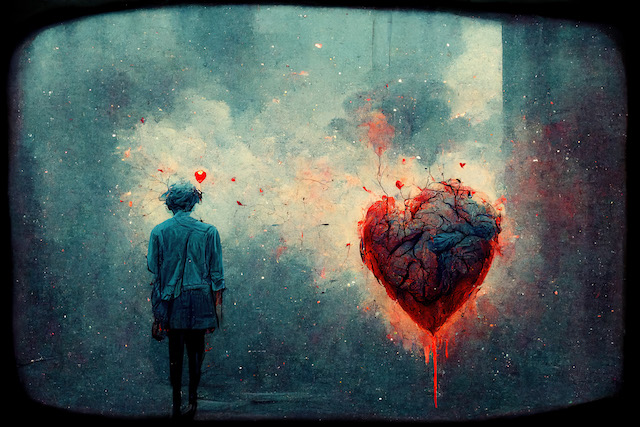

One’s home is grounding and so important to their inner stability. Divorce is like an earthquake leaving emotional rubble in the living room that a family must heal and recover from.

My “earthquake” happened when I was fifteen years old. There had been tremors before. My parents sometimes liked each other. But when they didn’t, there was a lot of shrieking in the kitchen and even worse, cold silences where they would walk by one another as if each one didn’t exist—a scary distance that gave me a stomachache.

My worst fear was that they’d divorce, but I decided if that happened, I could always just kill myself.

Thankfully, my plan never came to pass. But on that autumn day, after a tearful conversation on our beige sofa when my parents used the terrifying “D” word, I decided that I would never cry about it again and tell no one. Instead, I got on my bike and pedaled away my pain, my voice lost in spokes of sorrow. I didn’t eat enough for years hoping that swallowing less would lessen the pain.

The literature points out that living in a home with high conflict is more detrimental than divorce for all parties involved, so no matter how painful it is, separation is often the next right and healthy step.

Recent findings indicate that better adjustment after divorce correlates with less conflict before and after between the parents. So it’s the detrimental effects of conflict rather than the divorce itself that is an important mediating factor to consider.

Yet “nice” divorces without conflict and with excellent communication are rare. Most couples will divorce how they were married and bring the dysfunctional communication and marital issues into the divorce process. After deciding to divorce, things may become more stressful for families. But if the marriage doesn’t feel salvageable, separation provides hope for something healthier and happier that staying in an unhappy relationship may not provide.

Quickly, my father met someone new. And suddenly, I was meeting a lady in a big house that was neat, orderly, and had three teenagers. I was scared they wouldn’t like me. But they were nice to the curly-haired young girl who visited every other weekend.

My stepmother taught me to make a pie crust being careful the dough was as “soft as a baby’s bottom.” She bought me my first prom dress and called my father “dear,” and no one yelled. She never became my mother, but over the years, I had the security of two women who took care of me. And when she died on a cold Christmas morning thirty years later, I had finally learned to weep.

There is a strange sense of togetherness in divorce even if a family doesn’t realize it at the time. Parents grieve, don’t feel good enough, and often have guilt because of the children. Children grieve and can have guilt about not being good enough to hold parents together. No one is alone in the sorrow, and that mutual understanding can reduce a family’s disconnection and isolation.

The importance of home and family is never shattered; it is how to rebuild and find a sense of belonging in the new arrangement that is left standing. Often, that includes new partners, stepbrothers and sisters, or a smaller family of a single parent and child.

The uncertainty of the future with new family constellations is challenging. Yet tomorrow’s uncertainty is an issue that parents, children, and all of us grapple with throughout life. But with time we adjust, build new homes, and find safety and a sense of security once again.

The emotional toll on children often includes increased sadness, anger, and depression, as well as increased physical symptoms and academic challenges. But just being aware of these reactions and comforting, normalizing, and giving voice to a child’s experience can be healing.

We have to encourage everyone not to divorce from their emotions. My parents, at the time of the divorce, thought it would be a good idea for me to see a therapist. He was an old man sitting behind a big desk who asked me a lot of questions that I didn’t want to answer. I think I sat through the whole session but was very clear I’d never go there again!

It was only with leaving my family for college that I could get help on my own terms. My hunger for my true feelings had finally become more important than remaining hungry for food, which was how I had coped for years.

I walked into my therapist’s office, and she smiled and said, “Take a seat.” I finally had found true nurturance in a safe space where I could share my anger, sadness, and grief. It was that deep home inside all of us which is the tender place of truth.

The timeline for healing is different for everyone and every family. But it comes with grieving and an acceptance of the loss—like a death we never forget but learn to live with, and it becomes part of us and our life story.

Divorce may not be what we planned for, that fairy tale of happily ever after. And we can easily be hard on ourselves or hurt ourselves with destructive behaviors instead of facing our pain. But learning how to grieve, care for, and love ourselves through the difficult times brings a sense of peace and healing to the home inside. And that home isn’t defined by a mom’s or a dad’s house.