“There are years that ask questions and years that answer.” ~Zora Neale Hurston

At the age of thirteen, my childhood as I knew it came to an end. My parents sat my brother and me down at the kitchen table and told us they were getting a divorce. In that moment, I could acutely feel the pain of losing the only family unit I knew.

Although my teenage self was devastated by this news, it would take another twenty years for me to realize the full extent of what I had lost. And to acknowledge that I had never fully grieved this loss.

While divorce is so common in the United States, it is not a benign experience for children or adolescents. In fact, divorce is even considered a type of adverse childhood experience, or childhood trauma, that can have long-term behavioral, health, and income consequences. Children of divorced families have an increased risk of developing psychological disorders, attaining lower levels of education, and experiencing relationship difficulties.

However, not all divorce is equal and will impact children in the same way. And if the children still feel loved, protected, and supported by the parents following the divorce, this can act as a buffer against long-term harm.

But in many cases following a divorce, parents are not in an emotional or financial state to continue meeting the children’s needs at the same level as prior to the divorce. In these circumstances, children are less likely to receive the emotional support needed to properly grieve—which is what I personally experienced.

After receiving news that my parents were planning to divorce, I did begin the grieving process. I was in denial that they would actually go through with it. Then I felt anger that they were uprooting my entire world. And then after the anger settled, I remember pleading with them for weeks to stay together. But I think I got stuck somewhere in the stage of depression, never being able to fully reach acceptance.

Then, twenty years later, after a series of stressful life events, I realized how much the divorce of my parents still impacted me—and how I still had grieving to do. So, at thirty-two years old, I faced a childhood head-on that I had spent my entire adult life attempting to avoid. And I gave myself everything that the thirteen-year-old me had needed twenty years ago but had never received.

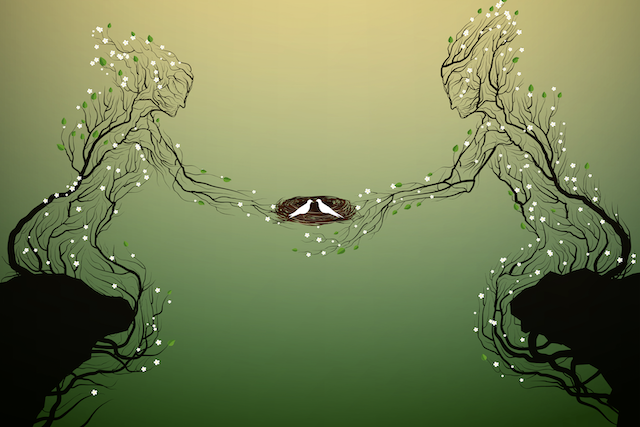

I gained social support through my husband, friends, and therapist. I showed myself compassion. And after two decades, I finally gave myself permission to grieve the childhood and family of origin that I never had and never will.

I believe the reason that divorce can be so harmful for children is because there is a prevalent belief that children are resilient and they’ll always bounce back. When provided the right support and care, this may be true. However, children don’t have the emotional maturity to manage their emotions on their own when experiencing such an intense loss. This is particularly true when the divorce precipitates or is accompanied by other types of adverse childhood experiences.

Since divorce can oftentimes lead to intense upheaval and disruption in the family structure, this makes children more susceptible to other types of trauma. Financial difficulties, abuse from stepparents, or a parent suddenly becoming absent can all amplify an already distressing situation for a child. And since children are programmed to rely on their parents for survival, what may seem like a mildly stressful incident for an adult could feel life-threatening for a child.

I never fully grieved and accepted my parents’ divorce because I lacked the social support I needed to do so. And since the breakdown of the family also led to a breakdown in parenting, I was focused on survival, not grieving. However, it took me many years to realize that my parents were also focused on survival, which can take precedence over ensuring your children are prepared for adulthood.

I know my parents did the best they could with the tools they had at the time. But it has been difficult to understand why a parent wouldn’t do everything in their power to shield their child from trauma.

I was not old enough to understand that it was mental illness and substance abuse that caused a parent’s partner to go into violent rages. My parents had to pretend everything was normal for their own survival—all while neglecting to consider the long-term impacts of trauma during such formative, developmental years.

To avoid the instability and chaos of the post-divorce homes, from the age of fourteen, I bounced around living from friend’s house to friend’s house. And by the age of sixteen, I had left school and was working nearly full-time in restaurants.

I didn’t have any plans for my life, but working gave me a sense of safety and an alternate identity. No one had to know that I was a teenager from a broken home living in a trailer park. They only cared that I came in on time and did the job.

Looking back, it’s clear that my desire to leave school and work was very much a means to gain some control over my chaotic and troubled home life. I felt as though I had to support and protect myself because I had no one to fall back on. And this has been a consistent feeling throughout my life.

When I began the process of grieving my parents’ divorce as an adult, I realized how many of my beliefs about the world and myself were connected to the aftermath of this traumatic experience.

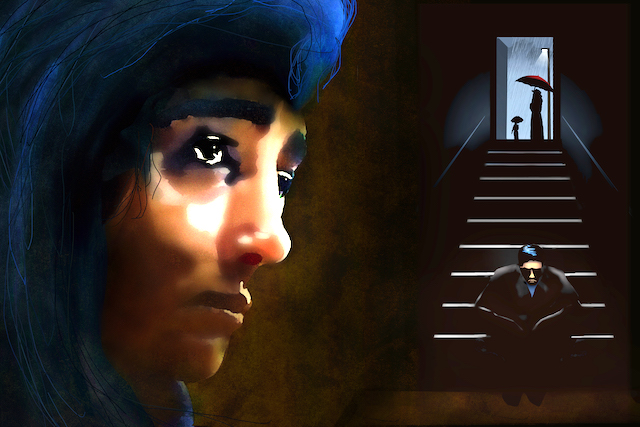

My early years instilled beliefs in me that the world is not a safe place—and that I’m not worthy of safety or protection. And it was through the process of grieving that I realized that the thirteen-year-old girl that feared for her safety was still inside me wanting to be heard and comforted.

I wanted to tell her that she had nothing to fear. But that wouldn’t be the truth. Because the decade following the divorce would be filled with intense distress and tumult. And she would be expected to endure challenges beyond her years.

While I couldn’t tell her that she would have nothing to fear, I could tell her that she would get through it with courage. And she would become an adult with the ability to love, and a devotion to the health and preservation of her own marriage. And that she would put herself through college and grad school and have a professional career and travel the world.

I could tell her that some stressful life experiences in her early thirties would open up wounds that she had kept closed for decades. But that she would be strong enough to constructively deal with her past and accept the loss of a childhood cut too short. And that through this journey, she would learn to forgive and show compassion—to herself and to others.

Grieving my parents’ divorce changed me. I’m no longer waiting for the other shoe to drop. And I’m no longer blaming myself for a truncated childhood. I’m also learning that the world is not as scary and unpredictable as I’ve spent my entire adult life thinking it was.

I’ve discovered that while there was a point in my young life when I experienced hardships that exceeded my ability to cope, I now have all the tools I need inside of me. And I know that it is possible to reach a point in life where you are no longer focused on surviving but rather on thriving.