“Grief is really just love. It’s all the love you want to give, but cannot. All that unspent love gathers up in the corners of your eyes, the lump in your throat, and in that hollow part of your chest. Grief is just love with no place to go.” ~Jamie Anderson

When I was seventeen, my dad died from depression. This is now almost twenty-two years ago.

The first fifteen years after his death, however, I’d say he died from a disease—which is true, I just didn’t want to say it was a psychological disease. Cancer, people probably assumed.

I didn’t want to know anything about his “disease.” I ran away from anything that even remotely smelled like mental health issues.

Instead, I placed him on a pedestal. He was my fallen angel that would stay with me my whole life. It wasn’t his fault he left me. It was the disease’s fault.

The Great Wall of Jessica

But no, my dad died by suicide. He chose to leave this life behind. He chose to leave me behind. At least, that’s what I felt whenever the anger took over.

And boy, was I angry. Sometimes, I’d take a towel, wrap it up in my hands, and just towel-whip the shit out of everything in my room.

But how can you be angry with a man who is a victim himself? You can’t. So I got angry at the world instead and built a wall ten stories high. I don’t think I let anyone truly inside, even the people closest to me.

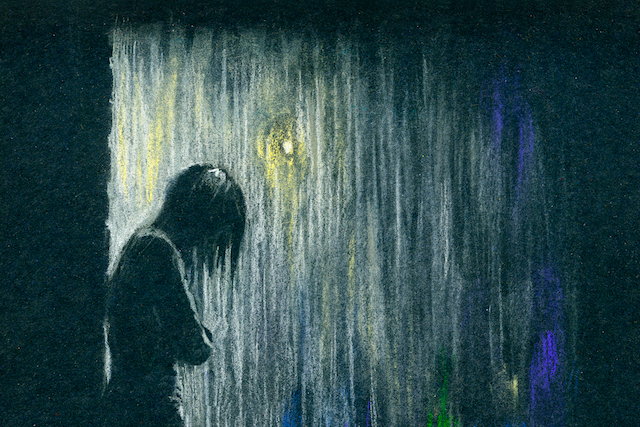

How could I? I didn’t even know what “inside” was. For a long time, my inside was just a deep, dark hole.

Sure, I was still Jessica. A girl that loved rainbows and glitter. A girl that just wanted to feel joyful.

And I was. Whenever I was out in nature. I didn’t realize it at the time, but whenever I was on the beach, in a forest, or even in a park, I’d be content and calm.

Whenever I was inside between four walls, however, I felt restless, lonely, and agitated. This lasted for a very long time. I’d say for about twenty years—which, according to some therapists, is a pretty “normal” timespan for some people to really make peace with the traumatic death of a parent.

But during that time, alcohol and partying were my only coping mechanisms. I partied my bum off for a few years. I’d drink all night until I puked, and then continue drinking. Couldn’t remember half of the time how I got home or what happened that night.

Hello Darkness, My Old Friend

Unfortunately, all that alcohol came with a price. I had the world’s worst hangovers—not only physically but also mentally. At twenty-one, hungover and alone at home, I had my first panic attack. Many more followed, and I developed a panic disorder.

I became afraid of being afraid. I didn’t tell anyone, because I was scared they would think I was crazy.

Those periods of anxiety never lasted longer than a few months. But they were usually followed by a sort of winter depression. In my worst moments, I felt like the one and only person that understood me was gone. I felt like nobody loved me, not as much as my dad did. And I did think about death myself. Not that I actually wanted to die, but at times, it seemed like a nice “break” from all the pain.

Acceptance and Spiritual Healing

Finally, in my mid-twenties, I went to see a therapist. She helped me tremendously and made me realize that the panic attacks were nothing more than a physical reaction to stress. Yet, it wasn’t until I did a yoga teacher training a few years later that I finally learned how to stop those panic attacks for good.

Wanting to know more about the mechanisms of the body and mind, I dove into mental and physical well-being, and started researching and writing about mental health.

I understand now that self-love, or at least self-acceptance, and a solid self-esteem are crucial for our mental health. And I know that people with mental health issues find it so, so hard to ask for help. Their lack of self-love makes them think they are a burden.

I understand that, at that moment, my dad didn’t see any other solution for his suffering than stepping out of this life. It did not mean that he didn’t love me or my family.

The pain from losing my dad actually opened the door for me to spiritual healing. It brought me to where I am now. It taught me to live life to the fullest.

It taught me to follow my heart because life is too precious to be stuck anywhere and feel like crap. And it made me want to help others by sharing my story.

I have accepted myself as I am now. I know that I’m enough. I’ve learned what stability feels like, and how to stay relaxed, even though my body is wired to stress out about the smallest things due to childhood trauma.

Let’s Share Our Demons and Kill Them Together

But honestly, the pain from losing him will stay with me for the rest of my life. And sometimes it’s as present as it was twenty years ago. I don’t feel like covering that up with some positive, “unicorny” endnote.

I feel like being raw, honest, and open instead. Depression and suicide f@cking suck. What I do want to do, however, is to help open up the conversation about this topic. I want to make it normal to talk about our mental health, as normal as it is to talk about our physical health.

There are way too many people living in the dark, due to stigmatization and fear. Life is cruel sometimes. And every single human on this planet has to deal with shit. It would be so good if we could be real about it and share our stories so other people can relate and find solace.

I do hope that my story helps in some way.