“Breathe. Let go. And remind yourself that this very moment is the only one you know you have for sure.” ~Oprah Winfrey

I tried to stay strong after my fifteen-year-old son Brendan died in an accident. It shattered my world. The shock of it numbed me but when that wore off, I knew I needed to be there for my husband and two other children. Zack and Lizzie were only ten and thirteen and needed my strength. So, I built a wall around my heart and pushed through my day. I went back to work, teaching piano students in my studio.

But at night my throat burned from unshed tears. My neck muscles ached from holding myself rigid. I had half-moon bruises across my palms; I didn’t even realize I spent the day with my hands clenched in fists, my nails digging into my flesh.

Still, I stayed strong. Until Matthew ran into my piano studio and I discovered the real meaning of strength.

Each week he burst into the room, eager to play me his new song. He was a six-year-old boy with freckles bouncing across his cheeks. He threw his bag onto the table, uncaring that books and pencils slid out. He wiggled onto the bench and grinned at me before crashing his hands into the keys.

He played me his own story about aliens and a spaceship that hopped from planet to planet. He threw his whole body into his song, attacking the keys until he built a wall of sound that screamed throughout the room.

I smiled. “I love your story.” I gave him a sticker that he proudly placed on his shirt. But then I reached for my lion.

Leo the Lion was a stuffed animal that sat on the shelf above my piano. He was so soft that students couldn’t resist reaching up and stroking his velvety fur. His arms and legs—filled with tiny beans—drooped over the shelf.

Sometimes, he sat on the side of the piano, listening to a student play when they felt a little shy. Other times, I put him on a student’s shoulders. Make him fall asleep, I’d whisper, a gentle reminder to keep their shoulders relaxed and down.

With Matthew, I reached for the lion so I could teach him how to play loud and soft. Playing soft requires a lot of control. Students lean in gently, their fingers brushing the keys, like tickling with a feather. They’re so tentative they barely make a sound. But not when it comes to playing forte.

Most students love to play loudly. They crashed their fingers into the keys, digging into the note until it sounded like a punch. I wanted the note to sound full and rich, but not like a scream.

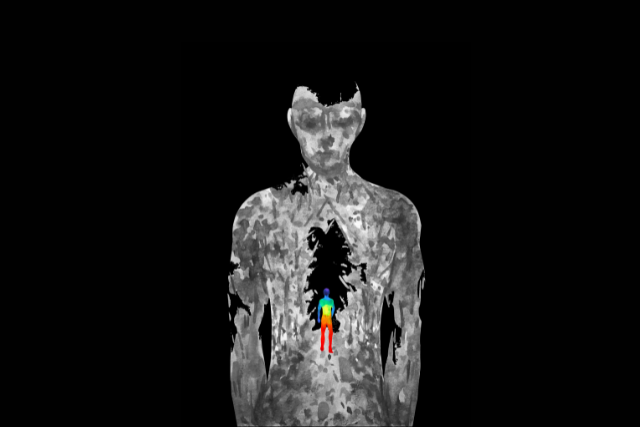

I pulled down Leo and wiggled him so that his arms flopped around. I lifted one lion arm up and let it drop down on its own. “Leo doesn’t try to attack the keys,” I said. “He just lets the weight of his arm fall into the keys.”

I let his paw fall a few times on Matthew’s arm so he could feel the weight. Then I put a rubber bracelet around Matthew’s wrist and gently lifted his arm up by the bracelet. I held it up in the air. “Don’t try to fight it when I let go. Just let your arm fall.”

It was hard for him to let me direct his arm. He couldn’t let it just flop around. “You have to give up control,” I said. “Let me move your arm and then just let it go.” After a few times, he surrendered to the weight of his arm and let it fall into the keys. He looked up at me and grinned.

“That’s the secret to playing forte,” I said. “Forte actually means strength in Italian. And in order to play a note with strength, we need to give up control. We lift our arm and then let go.”

And that’s when I realized I was doing strength all wrong

I tried to stay strong by controlling my grief. I stood tall and stiffened my shoulders, my muscles tight. I swallowed my sorrow until I could barely breathe. And still, I didn’t surrender to the weight of grief. I stayed strong. And if I couldn’t, I hid inside my house and let myself shatter. I refused to let anyone see me without my shields.

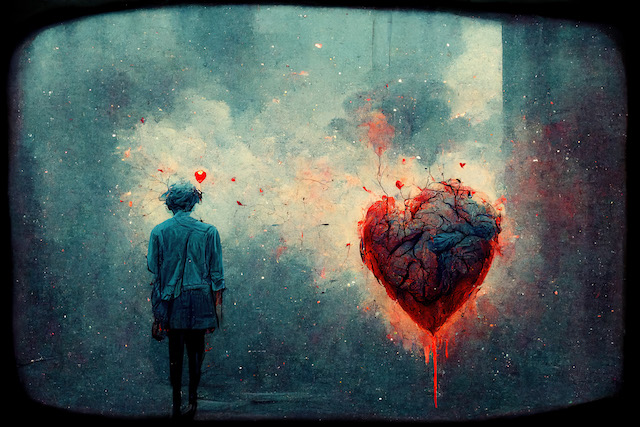

But Leo the Lion reminded me that I had the wrong definition of strength. Staying strong can mean surrendering to the pain. It can mean being strong enough to let go and show my heart even when it’s filled with sorrow.

I needed to learn how to let go. It didn’t come easy for me. Just like Matthew, it was something I needed to practice over and over.

I started with becoming more aware. I scanned my body for signs of tension, knowing it was a sign of emotions trapped within my tissues. I stayed patient with myself, just like I did when Matthew played with too much force. I reminded myself to be aware of the tension without judging it.

I no longer swallowed my emotions. Instead, I leaned into them, naming each one, acknowledging their presence. I felt the tension in my shoulders. Yes, this is grief. I felt the muscles in my arms quiver. Yes, this is anger. I felt my stomach tied in knots. Yes, this is anxiety.

Once I acknowledged my emotions, it became easier to release them. Some days, I meditated and then journaled. Or I walked in the forest, listening to the leaves whispering in the wind. I wrapped myself in a blanket and listened to music, sinking into each note until it melted away some of my feelings. And some days, I simply let myself sit in sorrow without judging it as a “bad day.”

I’m not perfect. There are days I forget and put on my mask of strength and pretend everything is fine. But just like my students, I’ve learned it’s a practice. When I forget, I remind myself to stay patient. And I keep Leo the Lion on my shelf as my reminder what strength really means. I stop trying to stay in control. I surrender to my feelings.

I stay strong by letting go.