“Be proud of who you are, not ashamed of how someone else sees you.” ~Unknown

“When was your last relationship?” my hairdresser asked as she twisted the curling wand into my freshly blow-dried hair.

“Erm, around two years ago.” I lied.

“Why did you break up?” she asked.

“Oh, he had a lot of issues. It wasn’t really working out.” I lied again.

I had gotten quite good at this, lying to hide my shame over being in my early thirties and never having been in a serious relationship. I had learned to think on my feet; that way, no one would ever call me out. The last thing I needed was people’s pity and judgment.

I sat in my chair thinking about what she might say. Should I have told her that I have never been in a serious relationship? Would she be compassionate or judgmental? Would she feel sorry for me and think there was something wrong with me? That was a risk I was not willing to take.

I felt so much shame and embarrassment around my relationship status that I would avoid discussions about it at all costs. Or I’d lie or get defensive with family and friends who would bring it up, to the point that they noticed it was a sore subject and would avoid asking about my love life.

I learned to recognize how shame manifested in my physical body—the anxiety I felt when someone would ignorantly ask when I would be having children, the rapid heartbeat when asked if I would be bringing a plus-one to gatherings, and the knots in my stomach when I would be invited places that would consist of mainly couples.

The shame I felt around my relationship status had always prevented me from speaking my truth because I was afraid I would be judged harshly.

I felt like someone with an addiction who was in denial. I was so ashamed that I couldn’t bring myself to say the words “I’ve never had a serious relationship” to anyone, not even my closest friends and family, despite them knowing deep down.

The Quest to Find Love

I felt aggrieved that I had gotten to my early thirties without ever being in a serious relationship. The creator didn’t love me; it had forgotten about me. I desperately wanted a loving relationship, as I was tired of being alone, and I wanted to experience true love.

I had a warped belief that being in love meant that I would feel happier, content, and life would genuinely be easier. After all, this is what we are told in fairy tales—the princess gets her knight in shining armor and they live happily ever after!

Over the years, I delved into the dating scene, trying dating apps, and keeping an active social life so I could meet people. Time went by, and I dated multiple unavailable men who ran when they sensed I wanted something serious.

This eventually got tiresome, and it took a toll on my self-esteem and confidence. I felt undesirable and not good enough.

I couldn’t understand what I was doing wrong! Was I being punished? I was well-educated, with a good career and prospects, and I wasn’t bad looking at all. And more importantly, I was considered kind, outgoing, and friendly by those who knew me.

Enough Is Enough

I was exhausted and frustrated and had no more energy left in me to keep looking for a good match.

I was so fed up with being met with disappointment and feeling bad about myself that I slowly began to give up on love.

I convinced myself that I would never find the right partner, that I wouldn’t experience the over-glamorized idea of love I had conjured up in my head from early childhood.

This only heightened my feelings of shame. It told me that not only was I not good enough to have a partner, I wasn’t capable of seeing something through until the end, and I didn’t possess the courage to ‘tough it out.’ Shame told me I was a bad person, unworthy of love.

Sulking into my pillow on a Sunday afternoon, I had a sudden thought: Maybe it’s not them, maybe it’s you. I got angry at this thought. How could I possibly be to blame? I’ve done nothing wrong. The only thing I am guilty of is wanting to be loved.

Another thought came: Maybe you can do something to change your experiences. This thought didn’t get me as angry, and after reflecting on it for a day or two, I concluded that I had to take some responsibility for the kind of men I was attracting.

I took a step back from finding ‘the one’ and put my energy and focus on working on myself. I concluded that most of the qualities I wanted in a man I didn’t even have in myself—for example, confidence and assertiveness.

Compassion Over Everything

I learned that shame can be ‘killed’ when it’s met with compassion, so I started being kinder and less critical of myself. I made a conscious effort to avoid negative thoughts, praised myself as often as I could, and tried not to be too hard on myself.

I confided in my close friends about the shame I felt around my single status, despite it taking much courage to do so. The more I admitted to people that I had never been in a serious relationship, the better I felt and the more I began to accept it.

Being vulnerable with those I loved was like a weight being lifted off my shoulders. What’s even better was that I wasn’t judged harshly or pitied as I anticipated, and instead, I was shown love and compassion.

I remember telling a new colleague that I hadn’t been in a serious relationship, and she said, “Me too.” My fear of how she would react quickly turned to relief that there were people just like me, that I had nothing to be ashamed of.

I was, however, choosy about whom I told my story to, as not everyone is deserving of seeing me at my most vulnerable. I knew I had to be careful because if I was not met with compassion and was judged and ridiculed, this could have exacerbated the shame I already felt.

Love is Love, No Matter Where It Comes From

I began to realize that love is love, and regardless of my relationship status, I had plenty of it. I didn’t need a partner to feel loved, and love isn’t less valuable because it doesn’t come from a relationship.

We can be shown love by our friends, family, colleagues, ourselves, and even strangers. This love is just as special and meaningful as the love you experience in a relationship.

With this in mind, I began to cultivate more self-love in order to boost my confidence and self-esteem. After all, the best relationship I’ll ever have is the one I have with myself.

I started being kind to myself and saying nice things about myself through daily affirmations. I also accepted compliments when I was given them, took time out for self-care, and put boundaries in place where needed.

As a result, my confidence and self-esteem grew, and I started to understand my worth and value.

Letting Go of the Need to Find Love

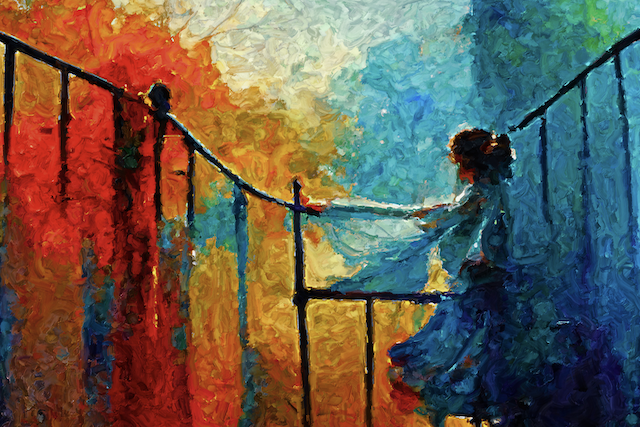

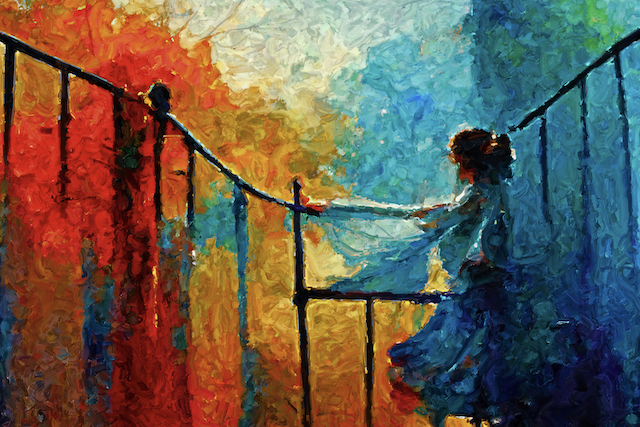

Over time, I began to let go of the need to find love. I hadn’t noticed that it had completely taken over every part of my being. I wasn’t closed off to finding love; in fact, I was very open about finding a potential partner. Only this time, I was okay with it if it didn’t happen.

I let go of the idea that someone would be coming to rescue me, and I concluded that I could be my own hero and best friend.

I let go of the idea that I needed to be in a relationship to be happy and made a conscious decision to be happy at that very moment. As a result, I began to feel free, liberated, and completely content with where I was in life.

When I let go, I noticed that the shame I felt around my relationship status had stemmed from fear. I was scared of what people would think of me because I wasn’t meeting the status quo. I was scared that I wouldn’t be able to start a family.

Where I Am Now

I still haven’t met ‘the one,’ and I’m okay with this. I am now at peace, joyful, and enjoying my life as it is in this present moment.

I no longer feel the shame I once felt around my relationship status or the fear that I have been left behind. I understand that I don’t have to be ashamed, as there are plenty of others just like me.

I choose to see my single status as my superpower. I get to use this time to learn and grow. I embrace and appreciate every moment of being single, as I know that when I do get into a relationship (which I will), I will miss moments of being single and having no one to answer to.

There are, of course, times when negative thoughts and behaviors try to rear their ugly head, but I simply remember who I am and ask myself, “Does this thought or behavior align with what I want or who I want to be?” If it doesn’t, I simply let it go.

For anyone reading this who’s experiencing feelings of shame and fear because they do not have a partner, remember you’re still worthy single, and you deserve your own compassion and love. Once you give these things to yourself, you set yourself free.