“Almost everything will work again if you unplug it for a while, including you.” ~Anne Lamott

I wake up anxious a little past 4am. My heart is beating faster than usual, and I’m aware of an unsettled feeling, like life-crushing doom is imminent. For a moment, I wonder if I just felt the first waves of a massive earthquake. Or perhaps those were gunshots I just heard in the distance.

But no, it’s just another night in my bedroom in the Bay Area, and everything is utterly fine. But somehow, my central nervous system isn’t so sure.

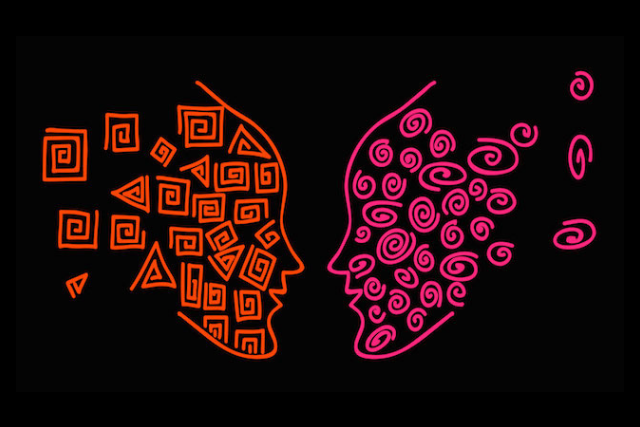

The problem is the thick swirl of news media, social media, and talk among friends I carry with me every day. It’s a toxic milkshake of speculation, fear, and anger that I consume, and it has me deeply rattled. I absorb this stuff like crazy.

I suspect I’m not alone.

I know for a fact that my anxiety isn’t just some vague menopause symptom, but the result of my deep immersion in the current zeitgeist. I know this because recently I left the whole thing behind for ten glorious days. I went to Belize, and left my phone and my laptop sitting on my bureau at home.

For most of that time, my wife and I lived on a small island thirty miles out to sea with only a bit of generator electricity. We avoided the extremely spotty Wifi like the plague. Instead, we woke with the sunrise, and sat on the deck outside our grass hut, watching manta rays swim in the shallow water below us and pelicans perch nearby. The biggest thing that happened every morning was the osprey that left its nest and circled above us.

It was life in slow-mo all the way. And it was transformative.

For ten entire days I didn’t think about politics or how America is devolving into an angry, wild place where public figures regularly get death threats, and social media has become the equivalent of High Noon with guns drawn.

The toxic interplay of who is right or wrong, or the future of our democracy ceased to exist as we sailed toward that island on our big, well-worn catamaran. In fact, by the time we reached our refuge, those tapes had disappeared altogether.

Instead, we swam and we rested. We snorkeled. We read. We had some adventures involving caves and kayaks, and we hung out with the other guests. The two Belizian women who cooked for us observed us Americans with our expensive toys, and they took it all with a grain of salt. In their presence, I could suddenly see how silly and overwrought all this intensity has become.

Ironically, when given the opportunity to present a gift to a school in one of Belize’s small seaside towns, I brought along a laptop and an iPad I no longer used. An elementary school teacher received the gifts with gratitude. Yet, as I gave them to her, I noticed I felt wary.

I could swear she seemed wary as well.

What new layer of complexity was I bringing onto these shores? And was it even necessary for life to go on happily and productively?

When we returned to the so-called civilized world, here’s what I immediately noticed:

1. I was now leery of all my previously trusted news sources.

Suddenly I could clearly see the anguished bias all around me, going in all sorts of directions left and right. The newsfeeds I’d previously consumed with abandon now seemed more biased than I’d realized. I was left with one option—either drop out and start reading the classics for entertainment, or proceed with caution.

2. I had more time to sit alone with nothing in particular to do.

Before my media fast, that was a bad idea. Hey, I had social media to check and emails to catch up on. The day’s events were going by in a high-speed blur, and I had to keep up. But now life had slowed to the pace of my emotions. I could breathe again. And so, for a while at least, I enjoyed spacing out.

3. My anxiety disappeared. For a while.

So did my knockdown ambition, and my desire to overwork. Everything had just … chilled. Enormously. For a while I slept easily. I no longer drove myself to do the impossible, and my to-do list now seemed balanced and reasonable. In turn, I no longer woke up with my heart pounding, nor did I have qualms overcome me during the day. Instead, I got ideas. Inspiration landed on me, and I was energized enough to pursue it.

4. Life became lighter and more fun.

Now I found my day-to-day routine to be far more delightful. It simply was, and for no particular reason. I laughed more. I found myself singing while I did chores around the house. Since I wasn’t consuming the same fire hose of media, I now had time to have more fun.

5. I complained less.

Now that I was unplugged, I found that I didn’t have to share my opinion on every last political matter happening around me. Nor did I need to engage in fights on social media. In turn, I didn’t lie awake as much, gnashing my teeth.

6. I thought about things I’d long forgotten.

Like my childhood. I tapped into long buried feelings sitting in that glorious deck chair of mine, like how it felt to be a vulnerable kid at school, and what joy I found in standing in the water, letting the waves rush my legs. I rediscovered the great internal monologue I have going all the time. It had long been forgotten.

7. I had more time just to hang with people.

This was, perhaps, the greatest gift of all. To quietly sit at a table, chatting over empty coffee cups with relative strangers, or perhaps my wife. There we all were, on our island for days on end. So we might as well talk, right? I found people to be fascinating once again.

In fact, I was discovering JOMO—the Joy of Missing Out. Turns out this is a thing. Those exact words were projected on the screen behind Sundar Pichai, CEO of Google, at a recent developer’s conference. Apparently even the tech people want to turn off their screens.

So one must ask the question: did all of this good stuff last?

In a word, no.

It’s been several months since this experiment ended, and I am, of course, back online. The pull is simply too great to ignore and avoid. Since I actually make my living online, disappearing off the grid is not even an option. And yet, I’ve learned a lot.

I no longer subscribe to certain reactionary newsfeeds. While I may be more out of touch, this is alarming material, guaranteed to not make me feel better. So no, I no longer read these emails. And I cherry pick what I read in my newsfeeds with care.

I no longer reach for my phone as soon as I open my eyes every morning. I also try not to check my email on my phone at all, something I often did while waiting in the Bay Area’s many lines. In fact, I’ve learned to leave my phone at home when I go out.

Instead, I chat with other people while waiting in the line, or I just look around. Or I zone out and enjoy what brain scientists call the “default mode,” the fertile, random, and enjoyable hopscotch the brain does while at rest. I realized now that I’d been missing that hopscotch. Instead, I enjoy the fertile luxury of a good daydream.

My late daughter Teal would have understood my need to drop out perfectly. Even at age twenty-two, she refused to have a smart phone. She embraced the world, eyes forward and heart engaged, making friends wherever she went. And she did so until her sudden death from a medically unexplainable cardiac arrest in 2012.

“Life is now,” she liked to say. Usually she reminded me of this as she headed out the door with her travel guitar and her backpack, on a spontaneous decision to busk her way across the other side of the world.

At the time, I couldn’t begin to fathom what she was talking about. “Too simplistic” I thought, dismissively, as I wrote it off to my daughter’s relentless free spirit. But as it turns out, Teal was right. So now I am left with this very big lesson.

Not only is life now, life is rich, random and filled with delight. The trick is to unplug long enough to actually experience it.

Illustration by Kaitlin Roth