Here’s what I know about grief: There is no measuring stick.

The loss of a mother, father, sister, brother (or all of the above), the loss of a husband, wife, lover, boyfriend, girlfriend, or life partner, the loss of a best friend, dear friend, or close friend, the loss of a mentor, teacher, guider, inspirer… Who’s to measure? Who’s to say how profoundly those losses may or may not break our hearts?

There are no rules.

The loss of a happy, loving relationship may be far easier to survive than the loss of a troubled one.

A lover may feel overwhelmed by sadness years after a husband remarries and starts a family.

A close friend may feel as much loss and sorrow as a best friend.

When a person dies, they may have 10, 100, 1,000 friends, or even more grieving them. When Judy Garland died, so many people in the gay community grieved her loss that it was a contributor to the Stonewall riots and the beginning of the gay rights movement.

At first, when you lose someone, friends, distant and otherwise, shower you with messages and cards saying things like “This, too, shall pass” and “You are strong; you will get through this.” The Jewish religion gives you a week to “sit shiva.” You cover the mirrors. (Who wants to look at such a sad face anyway?!) You wear slippers. People bring you casseroles. You are expected to spend an entire week crying.

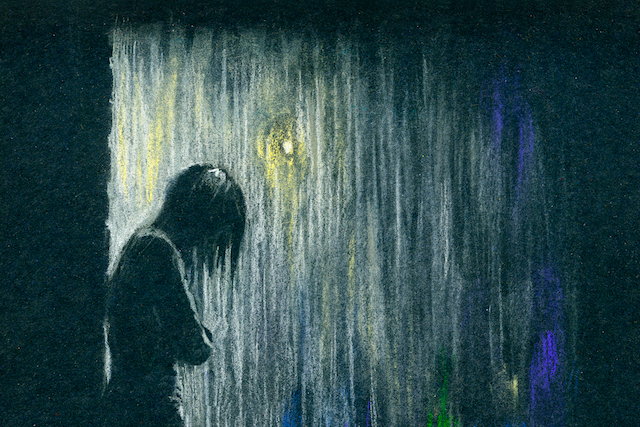

Two, maybe three weeks later, no one asks, “How are you feeling?” No more cards come in the mail. No more “May her memory be a blessing” messages on Facebook. Some friends avoid you for months, saying they “want to give you time to mourn.”

The overwhelming message feels like, “Times up! Move on! Cheer up!”

No one seems comfortable around grief.

Two weeks after I lost my mother, my girlfriend at the time decided to break up with me. She said she loved me (is that love?), but she loved the happy, fun, cheerful Rossi she met, not this sad, brooding, blonde mess.

I love NOT being with her anymore.

As much as people like to set limits, there is no time limit on grief.

I lost my mother, Harriet, thirty-three years ago. A Jewish mother’s love can be suffocating, yes, but also like a vast ocean of endless warmth. I wish I could swim in that ocean one more time.

“Get over it; she was just a friend.”Just?

I still mourn the loss of my mentor and friend Catherine Hopper, who passed away five decades ago. I was only eight years old when Catherine died. I can still smell the powder foundation she slapped on her face with abandon.

Some people feel they are in a grief competition. They downplay your grief by talking up their own (far superior) grief. What is this, the Grief Olympics? What is the medal, a lifetime supply of tissues?

2022 was my death year. I may always think of it that way. I lost my dear friend Kathryn, my best friend since childhood, Suzy, my friend and co-worker BB, and my sister, Yaya. I thought I was done with death after 2022, but I lost my brother, Mendel, on Halloween the following year.

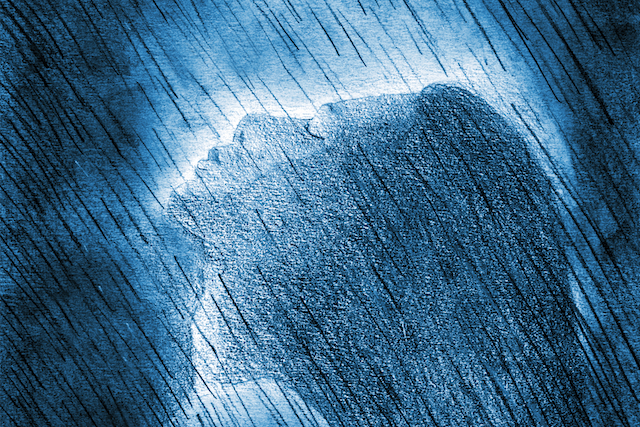

I’d like to say that I took the time to mourn each loss and move on before the next came, but it felt more like standing in the ocean getting toppled by a wave. Each time I came up for air, I was toppled by another.

Most people assumed I would have the hardest time losing my sister and brother. I had more trouble losing Suzy. She was the person I most likely would have been talking to about losing my sister and my brother. She’d known them both since we were children.

At fifty-nine years old, I found myself to be the last surviving member of my family. My mother used to call herself “The Last of the Mohicans.” At the age of forty-six, she was the last surviving member of her family. Yet another thing my mother and I have in common. This is not a baton I want to carry.

For eighteen years, BB was the person I could lean on professionally. If I were inclined to call in sick (something I rarely do), it would be okay because BB would be there. I think of our van rides to events together like the rings in a tree. I can trace where I was in my life and in our friendship by the depth of our van chats. Our first rides together, we talked about lemons, limes, and rosemary focaccia. Our last rides together, we talked about heartbreak and love.

My relationship with my brother, Mendel, was problematic and troubled, riddled with the hypocrisy that often accompanies extreme religion. In some ways, his loss has been the hardest. I mourn the brother I never had as much as the brother I did have.

I watched a movie on a JetBlue flight in which the main character was crying. His son asked him why he was crying, and he said, “Because I used to be a brother.” He had lost not only his siblings but also his identity as a brother.

I started crying too, much to the discomfort of the frazzled woman sitting next to me. I used to be a sister. I used to be a daughter.

In all the many words meant to support and comfort me these last few years, the ones that made me feel the most loved were when my partner, Lyla, decided weeks and months later to start each morning by saying, “Good morning, Honey. I love you. How is your heart?”

All had gone quiet, but not my morning messages: How is your heart?

These days, when friends have traumatic losses, I offer love, but more importantly, I check in with them a month or months later when society has revoked their permission to keep feeling sad and ask, “How is your heart?”

Life is hard. We like to say otherwise, because only Debbie Downers walk around saying things like “Life is hard.” But let’s face it: LIFE IS HARD.

We hope to have a life filled with love. Aren’t the best things in life about love? But the price of love is loss.

I like inside pockets, always have. Secret little places to tuck a pair of keys, a tissue, a lipstick, and a $20 bill.

My heart has inside pockets. I carry my mother there. She wanted to take my whole heart over, but I asked her to make room for Yaya, Mendel, Suzy, Kathryn, BB, and Catherine Hopper and her powdery foundation, too.

Folks talk a lot about the five stages of grief. I tell those five stages to screw off! No two people are alike. No two losses are alike. My grief is like no other grief.

My sister, Yaya, maintained a childlike abandon all of her life. She loved to put an “S” in front of words that started with “N.” It was one of the adorable Yayaisms I miss the most.

In the face of profound loss, I hear her voice. “S’NOT SNICE.”

In some ways, Yaya was the smartest person I knew.

That’s right, Yaya. S’not S’nice.