TRIGGER WARNING: This post briefly references sexual abuse.

“Never hold yourself back from trying something new just because you’re afraid you won’t be good enough. You’ll never get the opportunity to do your best work if you’re not willing to first do your worst and then let yourself learn and grow.” ~Lori Deschene

The year 2022 was the hardest of my life. And I survived a brain tumor before that.

My thirtieth year started off innocently enough. I was living with my then-boyfriend in Long Beach and had a nice ring on my finger. The relationship had developed quickly, but it seemed like kismet. Unfortunately, we broke up around June. And that’s when the madness began.

I believe it to be the extreme heat of the summer that somehow wrought this buried pain from underneath my pores to come up. Except the pain didn’t evaporate. It stayed stagnant, and I felt suffocated.

There were excruciating memories of being sexually abused as a child. Feelings of intense helplessness came along. I had nightmares every night, and worse, a feeling of horrendous shame when I woke up. All of this made me suicidal.

Before I knew it, every two weeks I was being hospitalized for powerful bouts of depression, PTSD, and the most severe anxiety that riddled my bones.

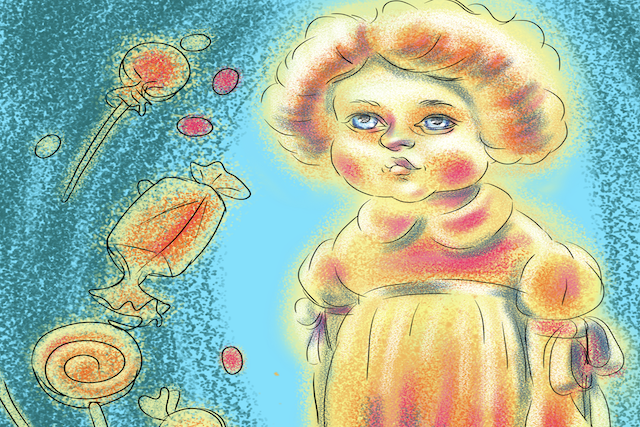

This intense, almost trance-like experience of going in and out of hospitals seemed like the only way to cope with life. I felt broken, beyond repair. I gained a lot of weight and shaved my head and then regretted it. My self-esteem plummeted.

I felt like I didn’t belong to society anymore. I’d had superficial thoughts like this before, growing up in the punk scene, but the experience of constantly being in and out of mental hospitals was beyond being “fringe.” I felt extremely alienated.

With many hospitalizations in 2022, I was losing myself. Conservatorship was now on the table. I was terrified and angry at the circumstances fate had bestowed upon me.

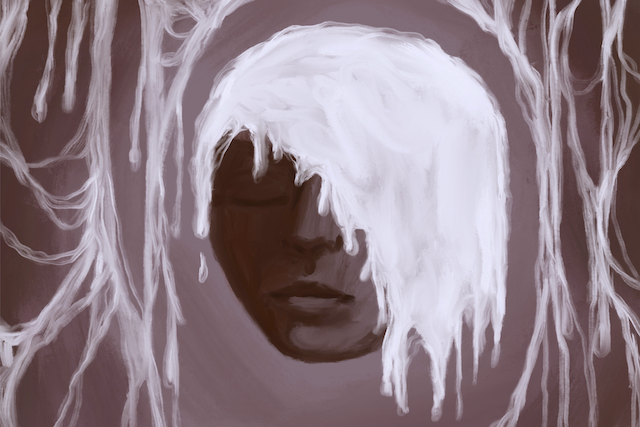

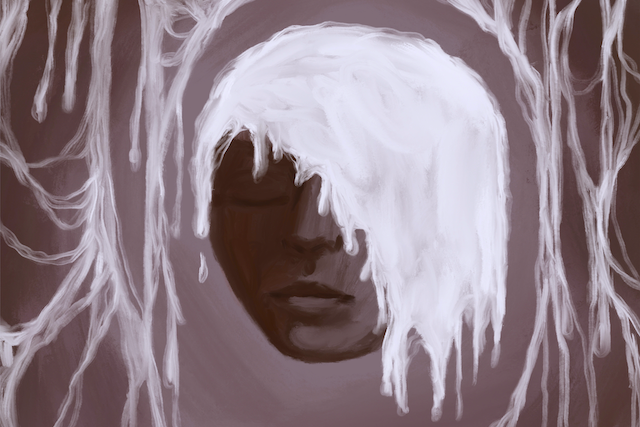

In my final hospitalization in December, I suffered tortuously. I was taken off most of the benzos I was on, and I was withdrawing terribly, alone in a room at the psych ward. My hands and feet were constantly glazed in a cold sweat.

I was so on-edge that every sound outside my door jerked my head up. The girl next door would sob super loud, in real “boo-hoos,” and do so for hours on end. It eroded me. I would scream at her to stop, but she would then cry louder.

If there was a hell on earth, this was it. I told myself, with gritted teeth, staring out the window, that this would be my last time in a psych ward. No matter how miserable I was, I would just cope with it. I didn’t want to deal with this anymore.

So I made a commitment to myself to really try to get better. Hope was hatched by that intense amount of pain. I knew I had a long journey ahead to heal, but that there was no other way but up.

After that final hospitalization, I joined a residential program that helped me form new habits. There was a sense of healing and community there. I felt a mentorship connection with one of the workers, who was a recovered drug addict.

I was glad I was finally doing a little better. I realized I shouldn’t have gone to the hospital so much and perhaps should have plugged into one of the residential places first.

This year has been easier as a result of sticking to treatment and addressing some of the issues that were plaguing me. I now have better coping mechanisms to deal with symptoms of PTSD, as well as some better grounding techniques.

As a result, I’ve been able to go back to work, despite still dealing with intense anxiety. For the first time in a while, I feel hopeful for my life. But I can’t help but getting hit with a barrage of thoughts before I go to work.

This whole thing I’m going through is commonly known as “imposter syndrome.” Basically, it feels like I don’t belong where I’m going in order to make the quality of my life better. I feel like a fake or a phony, afraid my coworkers will understand who I really am—someone who has struggled with PTSD and depression.

As a result, some days are more difficult than others when it comes to showing up at work. I’ll have mini panic attacks in the restroom. There’s an overwhelming feeling of surrealness.

Although I’m glad to have gotten out of the merry-go-round of doom, putting on a happy face and attempting to appear as a healthy, well-adjusted person is too much sometimes.

And I know it’s not just in my situation that people experience imposter syndrome. Some people that were once extremely overweight feel out of place once they’ve lost their extra pounds. Others who are the minority in race or gender where they work can also feel like they don’t belong.

I’ve come to realize this is a universal experience, the feeling of “not belonging.” It’s also a syndrome of lack of self-worth. I try to tackle this in baby steps every day.

Here are some things I try to live by to feel more secure where I’m trying to thrive.

I ask myself, “Why NOT me?”

There’s a Buddhist quote that suggests, when you’re suffering, instead of asking, “Why me?”, you’re supposed to humble yourself by asking, “Why NOT me?” But I think this is also relevant to feelings of belonging.

When you feel like you don’t belong, ask yourself, “Why NOT me?” Why wouldn’t you deserve to belong, when everyone else does, despite their varied challenges? This sort of thinking levels the playing field.

I remind myself of my worth.

I could spend hours thinking about why I’m not adequate or deserving. But I try to think about why I do have a right to be there. I deserve to get a paycheck like everyone else. I deserve to work, no matter what I’ve been through, and to value the sense of belonging offered through my coworkers.

I try to power through my inner resistance.

Many days this is more difficult than others, but I know if my greater goal is improving my life and feeling like I belong to society again, its worth challenging all the mental resistance I feel. I also know that my feelings will change over time if I keep pushing through them.

Cherish the times of connection.

There are times at work where I feel really connected to my coworkers, even though I doubt we have the same psychiatric history. I try to savor those times of connection because they keep me going. Since we are social beings, it is important to us to feel connected.

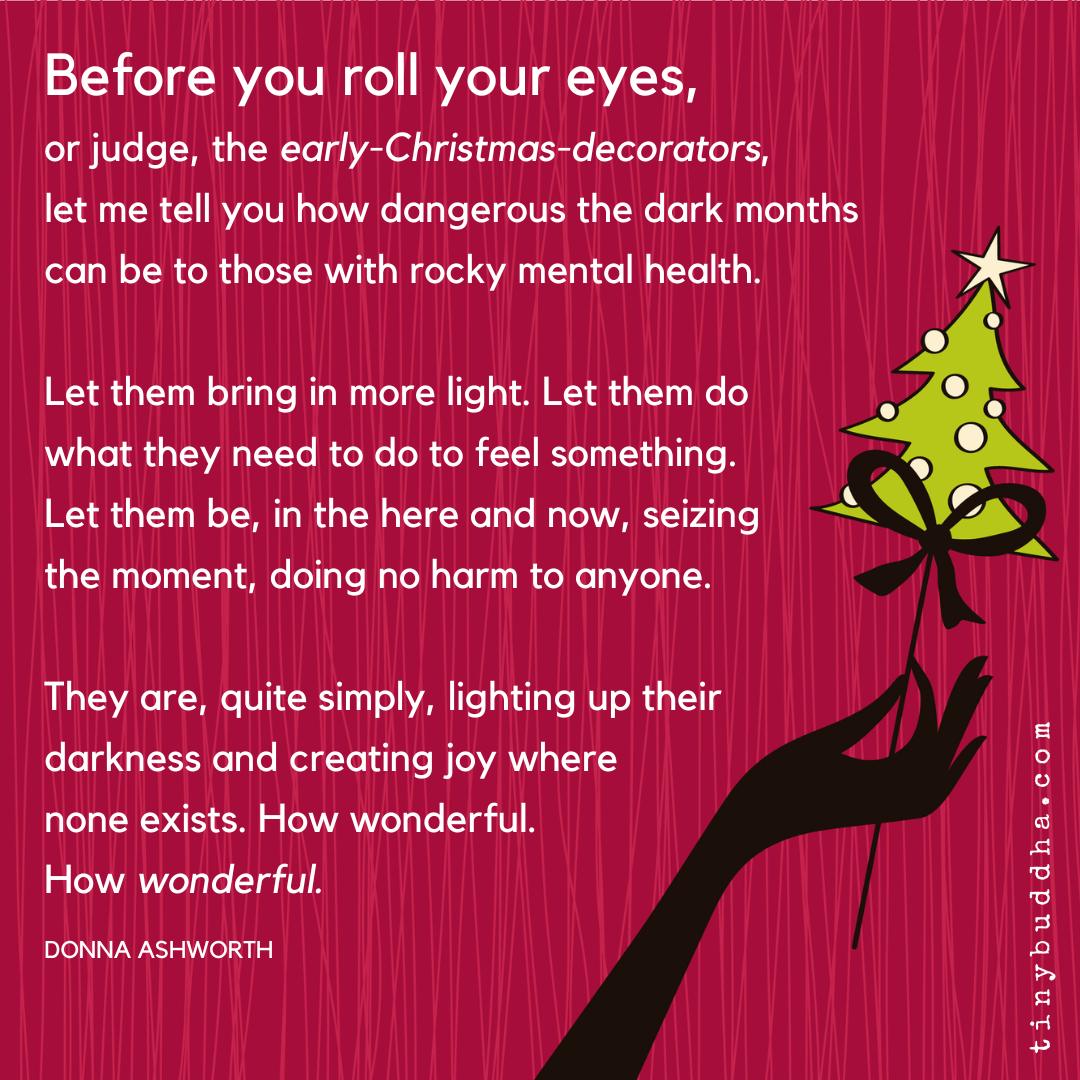

Take comfort in knowing this will fade.

Already, having just worked a few weeks at this job, my feelings of imposter syndrome are starting to fade. If I had known this would happen in the beginning, I wouldn’t have put so much anxiety on myself. If you’re going through this too in any capacity, just remember that the feelings are only temporary and will pass as you find your footing.

Make peace with your past.

Everyone has a past, some that may feel more shameful than others. But don’t conflate that with your right to belong and be a contributing member of society. Sure, some things are harder to rebound from than others, but that doesn’t mean that you can’t get past them. And that doesn’t mean you need to be defined or limited by your past challenges.

Validate your feelings of struggle.

Although it would be nice to just use denial to move forward, that’s not possible since you know the truth. You know what you’ve been through and how it’s affected you. I validate my experience in the struggle by going to support groups after work. That way I’m not gaslighting myself, pretending I’m fine. It’s just about knowing there’s a time and place for that unheard, marginalized part of yourself.

—

We all put on a brave face to be accepted, but we all deserve to belong, regardless of how we’ve struggled.

Don’t let your struggles define you. Instead, validate the fact that they have given you the strength to get where you are now.