“I have come to believe that caring for myself is not self indulgent. Caring for myself is an act of survival.” ~Audre Lorde

I’m a year out after completing chemo treatment for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and on my healing journey. Cancer is a nasty little thing and can rear its ugly head at any time again. So, to minimize those recurrent chances and to feel like I’m doing all that’s in my control, I’ve accepted that this healing path will be for the rest of my life.

I originally thought I’d be spending this first year rebuilding myself. And I have. However, I now see that this is a forever life path. Healing is a daily intentional practice, and I am on its continuous road.

Being proactive by incorporating healthy practices into one’s life isn’t a guarantee against illness, but it at least makes us feel like we’re taking charge and doing all that’s in our control to ward off disease and optimize our health and well-being.

I began exercising more than thirty years ago when my ex-husband moved out to begin divorce proceedings. My friend Gloria came by one day and pushed me to go to the local gym. She said it would be good for me. “Okay, I’ll try it out,” I said, “but I don’t think it’s for me.”

Well, fast forward… exercise became a life practice. Over the years my basement became home to a treadmill, stationary bike, free weights, a trampoline, bars, and a balance ball. The local gym is also my place of exercise, as is the boardwalk and nature trails. Like brushing your teeth and taking a shower, exercise is a daily living activity.

Healing encompasses a lot of factors. Sometimes it can feel overwhelming. Good enough must become a mindset and motto so we don’t beat ourselves up over occasional off days.

So what goes into a healing path?

Exercise is a must and a biggie.

Since that’s been a permanent structure in my life, I don’t have to work on that one. Like a tree trunk, it’s rooted deep in my ground. When the walking, biking, weightlifting, yoga postures, hoola hooping, or trampolining don’t take place for a few days, my body calls out, “Move me, twist me, stretch me, strengthen me.”

I have now added a new piece to my exercise: HIIT (high intensity interval training). Twenty minutes of HIIT a few times a week is indicated as an anti-cancer workout. And my dream and goal of ballroom dancing is being realized once again, as I’ve excitedly resumed my lessons that I started shortly before I was diagnosed. Movement comes in many forms.

Contemplative practices are inner forms of reflection and calming activities.

Meditation and breathing exercises, journaling, and time in nature are all soothing and quiet activities, bringing us back to ourselves. We listen to and feel what’s inside, what may be bubbling up, what our gut is telling us. We put aside the external distractions to promote the engagement of our calming parasympathetic nervous system.

For, as we all know and feel, as our anxiety levels have skyrocketed, we live on high alert all the time, fighting off the invisible tigers, as our fight-or-flight response is continuously engaged. We don’t have to be a guru meditator, but giving ourselves a few minutes a day to just be, sitting in quietude and breathing deeply, is a natural antidote to stress and a huge release of cortisol. And as we know, stress is a big contributing factor in illnesses.

Our lives are lived in a state of perpetual busyness and hecticness as we push ourselves toward productivity and perfection; therefore, we must prioritize activities that counter that busyness and bring us back to our selves. We oftentimes want to drown out our pain with distractions and busyness, but it catches up with us one way or another.

Eat to live becomes a mindset for a lifestyle of healthy eating.

We are gifted with a body that requires food to function well. As I am not a nutritionist, I’m not dishing out dietary advice. My new level of healthy eating is nature’s foods and limiting inflammatory, processed foods and sugars.

Before cancer, I had always been a big ‘nosher.’ Entenmann’s cakes, cookies, potato chips, Dr. Pepper soda, and ice cream were my after-dinner desserts. I cut most of this out years ago when I got ulcers and had reflux and irritable bowel.

One of my best takeaways from my trip to the Amazon was our hiking guide in the jungle, who said, “The jungle is our supermarket and pharmacy.”

The people there, as in many poorer countries, have very low rates of cancer and heart disease. Their food is plant-based, along with some fish and meat. And look at the Blue Zones, the places in the world where the people live the longest and healthiest. Those purple potatoes go a long way for them.

Making intentional food choices becomes a habit, giving ourselves the good stuff to fuel our body. This can be a harder part of the lifestyle to keep up with, as food preparation and shopping become a focal point. And for someone like me who’d rather be anywhere but the kitchen, this is definitely more difficult. It is an ongoing process for me.

The bigger purpose and mindset keep me on track. My guiding mindset is this: My body took care of me through my chemo treatment, and now it is my duty, in gratitude, to take care of it. I am paying it back for how it kept going and didn’t break down; it didn’t break me. So I look to feed it well.

I’ve upped my healthy eating to another level. My one square of dark chocolate each day satisfies my chocolate craving, and it has no sugar. I’ve developed a taste for this 100% dark chocolate. Practice and repeat. And whereas I used to choke down one piece of broccoli or asparagus, I now eat many pieces with my meal. Yay to baby steps of becoming more of a vegetable eater!

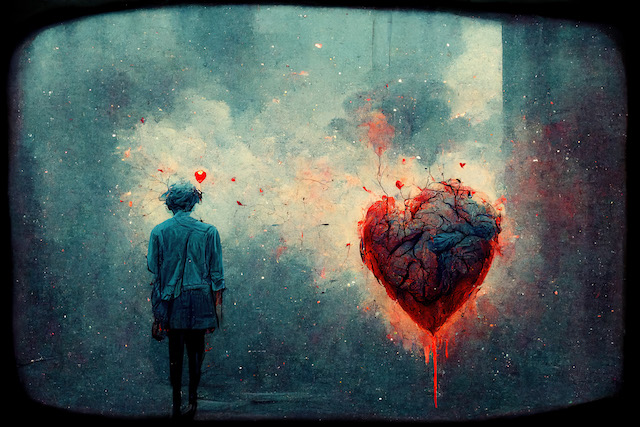

Inner psychological work is a new one for me.

I’ve been to numerous therapists throughout my adult life to deal with different circumstances, but now my therapy has taken on a whole new level and direction. During my treatment, I knew I wanted some type of support but did not want to join any support group or go to regular therapy again. I found, on this site actually, a creative arts therapist with whom I’ve been doing therapy like never before.

My goal, besides coping through the chemo treatments, was healing myself from the inside out. I had an intuitive sense that I needed to clear out my whole gut and center area of my body where the lymphoma had appeared. Get rid of the cobwebs that had taken root in there and work through past resentments, upset, anger, hurt, and all the rest of those toxicities.

Art, instincts, and unconscious work were all at play in this therapy, and continues today; uncovering and working through stuff that I never looked at like this.

—

This is my new life, beyond the simple wording of self-care. It’s focused and purposeful care of body, mind, heart, and soul.

It’s work, but after a while it feels really good to be doing this with the big purpose of optimizing our well-being so we can live our best life.