“Jerry, there is some bad in the best of people and some good in the worst of people. Look for the good!” ~George Chaky, my grandfather

I was seven when he said that to me. It would later become a guiding principle in my life.

My grandfather was twenty-one when he came to the US with his older brother, Andrew. Shortly afterward, he married Maria, my grandmother, and they had five children. William, the second youngest, died at the age of seven from an illness.

One year later they lost all of their savings during the Great Depression of 1929 when many banks closed. Two years afterward, my grandmother died from a stroke at the age of thirty-six.

As I grew older and learned about the many hardships my grandfather and family of origin had endured, his encouragement to look for the good in people would have a profound impact on me. It fueled a keen interest in trying to understand why people acted the way they did. In retrospect, it also had a lot to do with my becoming a therapist and author.

Easier Said Than Done

As a professional, I am able to objectively listen to my therapy clients’ stories with compassion and without judgment. However, in my personal life, I’ve often struggled to see the good in certain people, especially some elementary school teachers who physically and emotionally abused me and male peers who made fun of my small size.

In my youth I often felt humiliated, but not ashamed. I knew that for them to treat me that way, there must have been something wrong with them. But it still hurt.

I struggled with anger and resentment for many years. In my youth, I was taught that anger was a negative emotion. When I expressed it, certain teachers and my parents punished me. So, I stuffed the anger.

I Didn’t Know What I Didn’t Know

When I was twelve, I made a conscious decision to build walls to protect myself from being emotionally hurt. At the time, it was the best that I could do. Walls can give one a sense of safety, but walls also trap the pain inside and make it harder to trust and truly connect with others.

About that same time, I made a vow to myself that I frequently revisited: “When I get the hell out of this house and I am fortunate to have my own family, I will never talk to them the way my parents talked to each other and my sister and me.” I knew how I didn’t want to express my emotions, but I didn’t know how to do so in a positive and healthy manner.

Stuffing emotions is like squeezing a long, slender balloon and having the air, or anger, bulge in another place. In my late twenties, individual and couples counseling slowly helped me begin to recognize how much anger and resentment I had been carrying inside. They would occasionally leak out in the tone of my voice, often with those I wasn’t angry with, and a few times the anger came out in a frightening eruption.

“Resentment is the poison we pour for others that we drink ourselves.” ~Anonymous

I heard that phrase at a self-help group for families of alcoholics. After the meeting, I approached the person who shared it and said to her, “I never heard that before.” She smiled and replied, “I’ve shared that a number of times at meetings where you were present.” I responded, “I don’t doubt that, but I never heard it until tonight!”

The word “resentment” comes from the Latin re, meaning “again,” and sentire, meaning “to feel.” When we hold onto resentment, we continue to “feel again” or “re-feel” painful emotions. It’s like picking at a scab until it bleeds, reopening a wound.

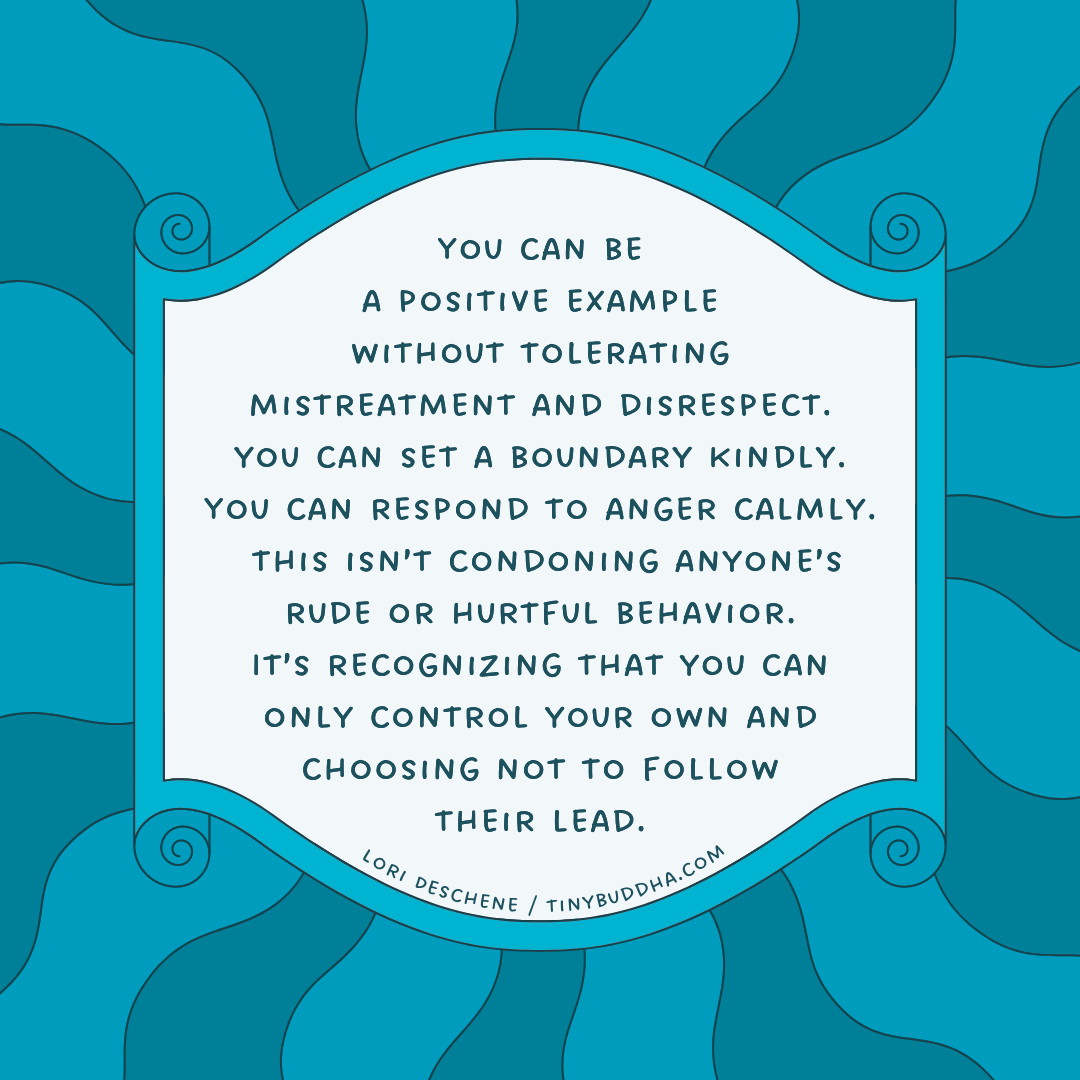

Nowhere have I ever read that we should like being treated or spoken to unfairly. However, when we hold on to resentment, self-righteous indignation, or other uncomfortable emotions, it ties us to the past.

Holding onto resentment and grudges can also increase feelings of helplessness. Waiting for or expecting others to change gives them power over my thoughts and feelings. Many of those who I have held long-standing resentment for have died and yet can still have a hold on me.

When we let go of resentment, it frees us from much of the pain and discomfort. As author John E. Southard said, “The only people with whom you should try to get even with are those who have helped you.”

I’ve continued to learn how to set healthier and clearer boundaries without building walls. I’ve learned that I don’t have to accept unacceptable behavior from anyone, and I don’t have to go to every argument I am invited to, even if the argument is only inside my head.

Still, for a long time, despite making significant progress, periodically the anger and resentment would come flooding back. And the thought of forgiving certain people stuck in my craw.

When people would try to excuse others’ behavior with statements like “They were doing the best they knew how,” I’d say or think, “But they should never have become teachers” or “My sister and I had to grow up emotionally on our own!”

Forgiving Frees the Forgiver

For a long time now, I have started my day with the Serenity Prayer: (God) Grant me serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference. It has helped me try to focus on today and what I can control—how I think, feel, and act. Sometimes I get stuck, and all I can say is, “Help me let go of this anger.”

“When we forgive, we heal. When we let go, we grow.” ~Dalai Lama

I frequently hear the voices of many people who have helped, supported, and nourished me. I hear my wife’s late sister, MaryEllen, a Venerini nun, saying, “Jerry, the nuns treated you that way because that was the way they were probably treated by their superiors.” She validated my pain and planted another seed that slowly grew.

I’ve also heard that “hurt people hurt people.” At times, I would still lash out at innocent people when I was hurting. I desperately wanted to break this generational cycle. I’ve learned that I don’t have to wait for other people to change in order to feel better.

I am learning that everyone has a story, and I can practice forgiveness without excusing what they did or said.

Forgiving is not forgetting. Forgiving liberates me from the burden of resentment, helping me focus on connecting with supportive people and continuing to heal. Letting go of resentment cuts the ties that bind me to the past hurts. It helps me be present today where I can direct my time and energy toward living in the present instead of replaying old pain.

For the past year I have made a conscious effort to start each day by asking my Higher Power, whom I choose to call God, “Help me be grateful, kind, and compassionate to myself and others today and remember that everyone has their own struggles.” This has become one of the biggest turning points in my travels through life.

You Can’t Pour from an Empty Cup

I have learned that taking care of myself is one of the most effective ways to stop resentment from building up. When I neglect one or more of my needs over time, I’m quicker to snap, less patient, and more likely to take things personally. Who benefits from my self-neglect? Not me, and certainly not my spouse, children, coworkers, or others. When I am H.A.L.T. (hungry, angry, lonely or tired) or S.O.S. (stressed out severely), I usually don’t like being around me either.

Self-compassion also weakens resentment’s hold, making it easier to be compassionate with others. Remembering that we’re all works in progress helps me treat myself and others more gently.

I often think about my grandfather’s words, “Look for the good.” Self-care and self-compassion help me to see the good in myself as well as in others. I can dislike someone’s actions or tone of voice and also recognize they’re not really about me.

I actually have a Q-tip (representing “quit taking it personally”) taped on my desk to remind me that someone else’s actions or words are likely the result of their own struggles. It helps me to “catch myself,” and instead of taking things personally, I try to remember that everyone has a story.

Gratitude Puts Everything in Perspective

There are days when I am faced with great or even overwhelming challenges, when it would be easy to default to anger—with other people or with life itself. On those days, I might notice a beautiful sunrise or feel touched by the love and kindness of others. Practicing gratefulness helps me to see life as both difficult and good. It is like an emotional and spiritual savings account, building reserves that help me to be more resilient during the rough patches in life, even when I feel wronged.

Specifically focusing on what I am grateful for each day also helps me heal and gives me periods of serenity. It empowers me to try to approach my interactions with others in a warm and caring manner while respecting my and their personal boundaries, which keeps small misunderstandings from growing into resentment.

Gratefulness and compassion toward myself and others take practice. It’s not a one-and-done thing. It’s like learning any new skill—the more I practice, the more it becomes a positive habit and feels more like second nature.

Without repeated practice, old, undesirable thoughts and patterns can come back. When I neglect self-care, I am most vulnerable to quickly regress.

I also need to be vigilant when things seem to be going well within and around me. I can become overly confident, trying to coast along and slack off from practicing gratitude and compassion.

I have been unlearning many things that no longer work for me. I have unlearned “Practice makes perfect,” replacing it with “Practice makes progress, and I will do my best to continue to learn, grow, and be grateful, one day at a time.”

I don’t always get it right, but every time I choose compassion, understanding, or gratitude over resentment, I am more at peace and more connected to everyone around me.